– Vladimir Dedijer –

Encirclement of partisan units in the Neretva and Rama valleys — Chetnik concentration on the left bank of the Neretva — Chetniks as the main enemy in the war — Contradictions in the March negotiations — German documents on the negotiations — Koča Popović’s opinion — Tito, March 29, 1943: “Do not engage the Germans” — Uglješa Danilović’s diary — A conversation with Tito — My hypotheses on the March events — The Fifth Offensive — Tito’s wounding.

While plans for an invasion of Yugoslavia were being drawn up in London and Washington, a decisive battle took place in March 1943 in the valleys of the Rama and Neretva rivers between Tito’s forces and German, Italian, Ustaša and Chetnik units. It was perhaps the most critical month of the Yugoslav revolution. The fate of the main operational group, led by the Supreme Headquarters and Tito himself, depended on the outcome of this battle.

Tito had around 20,000 fighters, but troop movements were hampered by the need to protect 4,000 wounded who were being transported through the Bosnian mountains in the harsh winter. In addition, close to 20,000 refugees were in the area alongside the army and the wounded — mostly elderly peasants, women and children fleeing their homes before the enemy, though the initial number of refugees had been 50,000.

From the north, the 717th German Division was advancing into the Rama valley. Tito ordered a counter-offensive, and at Vilića Guvno, the 737th Regiment of the 717th Division and four Ustaša battalions were crushed. The enemy was pushed back towards Bugojno and the partisans took Gornji Vakuf. Both sides suffered heavy losses. Several German soldiers and non-commissioned officers were captured, along with one major.

In the meantime, reports arrived that 20,000 Chetniks under Draža Mihailović had concentrated on the left bank of the Neretva, ready alongside Italian units to deliver a fatal blow to the partisan forces.

It should be noted that the Supreme Headquarters did not have a well-organized intelligence service to track the movements and plans of enemy units. Furthermore, it must be taken into account — a fact revealed only at the end of the war — that the German listening service intercepted all radiograms between the Supreme Headquarters and individual partisan divisions, decrypting them immediately. As a result, the German command knew precisely where the partisan units were headed and what forces they had.

Tito ordered units of the 2nd Proletarian Division to cross to the left side of the Neretva — where Chetniks were entrenched in bunkers — during the night of March 6-7. Over a destroyed bridge, Dalmatian and Serbian partisans climbed up, holding unscrewed grenades in their teeth, which they threw into the first Chetnik bunker. The Chetniks — mostly forcibly mobilized peasants — fled immediately, and that very night three battalions of the 2nd Dalmatian Brigade and three battalions of the 2nd Proletarian Brigade crossed the swollen Neretva, forming a bridgehead. The Chetnik commanders recovered from the initial shock and established a new defensive line on the slopes of Mount Prenj. However, partisan reinforcements arrived, and they went on the offensive, continuing to push the Chetniks towards the upper course of the Neretva and Glavatičevo.

Near Glavatičevo, and then near Kalinovik, Draža Mihailović’s Chetnik units suffered a complete defeat. Mihailović never recovered from that serious military blow, and in essence, this marked the beginning of his rapid political decline. He urgently requested military assistance from London. Radio London replied during a broadcast — in which messages were read out — with the words:

“Victory is not won by shining weapons, but by the heart of a hero!”

I happened to stop by Tito’s place when we heard that broadcast. Despite all the worries about the wounded, we had a good laugh. I remarked that it was hard to be a friend of the English.

In the Neretva valley, near Jablanica, some Chetnik officers were captured, and documents were found on them detailing cooperation with the Germans, Italians, Domobrani and Ustaše in this operation. A Chetnik order was also intercepted confirming Draža Mihailović’s collaboration with the Germans, Italians, Domobrani and Ustaše.

On March 1, 1943, I recorded the following in my Diary:

“The capture of the order issued by the ‘Main Staff of the Chetnik National Army for Montenegro and Herzegovina,’ headquartered in Mostar, is of extraordinary significance. The order was signed by Bajo Stanišić, and we seized it from a second lieutenant named Dragićević, who was heading to the front line with two escorts. Due to the negligence of a battalion commander in the 2nd Dalmatian, the Chetniks managed to escape while being transferred from the brigade to the division headquarters, but the order remained. It is one of the most important documents we’ve seized so far — but also the most shameful. At the end of the order, it states: ‘Last night, London approved cooperation with 33.’ This document reveals the code: ‘11 are the Germans, 22 the Italians, 33 the Ustaše, 44 the Domobrani and 55 the Muslim militia.’

“The same order instructed Chetnik forces to attack us on February 27. It also mentions coordination with the German air force.

“We had known before who the so-called Yugoslav government in London was, but this bloodshed wounds us especially deeply at this moment. It openly endorses collaboration with the Germans and Ustaše to have our wounded slaughtered.

“The role of the British government is shameful. Its radio station is being used to transmit such orders, while we are tearing up the railway line that is of vital importance to British and American forces in Africa.

“This will only further embitter our fighters and our people. The real war will begin when we drink London’s blood. Dogs among dogs. But we must remain silent. We must look at things dialectically. In international relations, we must assess the situation in context. Here, contradictions are at their sharpest. But global developments influence the state of our country. Then each of our fighters will take great satisfaction in returning like for like to those bandits from London.”

Because of this, a belief formed within the Supreme Headquarters and among the partisans that the Chetniks would become the main force in any future Allied landing in Yugoslavia, with the goal of preserving the capitalist system, centralist rule and monarchy. For that reason, Tito considered them the primary threat to safeguarding the achievements of the National Liberation War. He expressed this view in a communiqué dated March 30, 1943, sent to the Staff of the 1st Bosnian Corps. This document is held in the archives of the Military History Institute of the Yugoslav People’s Army, registry number 14-2 k 7, and was published in 1959 in the second volume of the Collection, on page 360:

“In light of the fact that Draža Mihailović has mobilized all forces from Montenegro, Herzegovina, the Sandžak, eastern Bosnia, etc., and had already in December reached an agreement with the Italians, Germans and Ustaše for a joint major offensive against us — which began in January this year — we have decided to direct all our forces towards crushing and destroying this traitorous gang, which represents the greatest threat not only to the National Liberation War, but to the future as well. In the battle on the Mostar-Konjic sector, those gangs caused us the most trouble. They numbered around 12,000 and occupied all the heights on the left side of the Neretva so that we were completely encircled in the river valley. Only thanks to the kind of heroism never before seen in the history of warfare were we able to heavily defeat the Germans at Vakuf, the Italians, Germans, Ustaše and Chetniks at Konjic, and rescue 4,000 of our wounded. This battle lasted for six weeks and our losses were very high.”

I gathered extensive material on the so-called peaceful relations with the occupiers during the war from 1941 to 1945. In the laws of war, “peaceful relations” refer to negotiations between warring parties while hostilities are ongoing — concerning, for example, the burial of the dead, ceasefires to protect civilians and similar matters. From the very first day of our uprising, the partisans held talks with the occupiers on prisoner exchanges, the treatment and feeding of enemy prisoners and so on.

In early September 1942, the Supreme Headquarters carried out a prisoner exchange — a group of German officers working in Livno on mining operations was exchanged for a group of arrested communists and captured partisans. This exchange took place on September 5, 1942, after which regular contact was established with German representatives for prisoner exchange on other fronts.

During negotiations near Livno on November 17, 1942, discussions focused on the exchange of prisoners — particularly German industrial experts captured during the liberation of Jajce. One of the German representatives, engineer Hans Ott, after concluding the discussions on the prisoner exchange, raised new topics that went beyond the usual scope. He proposed the creation of “a special reserve for Orthodox Christians” — that is, a designated area where no military operations would take place.

In major battles on the Neretva and in the northern sector towards Bugojno, our units captured Major Strecker, commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 738th Infantry Regiment, part of the 717th Infantry Division. On March 5, Major Strecker sent a letter from his headquarters to his division in Sarajevo, addressed to the German Plenipotentiary General in Croatia, Gleise Horstenau, in which he proposed resuming talks between the Supreme Headquarters and German occupation forces. The Germans responded promptly, and the Supreme Headquarters granted full negotiating authority to Milovan Đilas, Koča Popović and Vlatko Velebit. The authorization, signed by the acting chief of the Supreme Headquarters, Velimir Terzić, explicitly stated that the discussions would cover the following topics: “exchange of prisoners, the application of international wartime law by German military authorities towards the National Liberation Army and, thirdly, all other matters to be raised by the delegation and previously discussed in Livno on November 17, 1942, with Captain Heis during the prisoner exchange.”

The German command replied on March 10 that it agreed to open negotiations and proposed that representatives of the Supreme Headquarters arrive in Bugojno on March 12, as indicated in the document below:

“The German Command is prepared to receive one of your delegates. The proposed date is March 12, 1943. Meeting place in Bugojno.

“The delegation is guaranteed complete safety. Our troops have been instructed to allow safe passage for no more than three delegates, who will carry white flags, and to escort them to the nearest German Command.

“Delegation route: Rama — Prozor — Gornji Vakuf.

“Staff Major (Barth)”

The talks did not take place in Bugojno, but in Vakuf, on March 11 from 9:30 to 11:00 a.m.

However, regarding the March negotiations — their initiation, the content of the talks and the conclusions reached during meetings between the German military command and representatives of the Supreme Headquarters — there are major disagreements, as we will see in this chapter.

The acting Chief of the Supreme Headquarters, Velimir Terzić, claims that the initiative for the negotiations came from Tito himself after receiving initial reports that he was surrounded with the wounded, refugees and the army — from the north by German and Ustaša troops, and from the east and southeast by Chetnik-Italian forces. Under those difficult circumstances, Terzić believes, Tito was seeking a temporary reprieve.

However, in the book Wartime, Đilas writes that only Tito, Ranković and he himself were aware of the negotiations and their content.

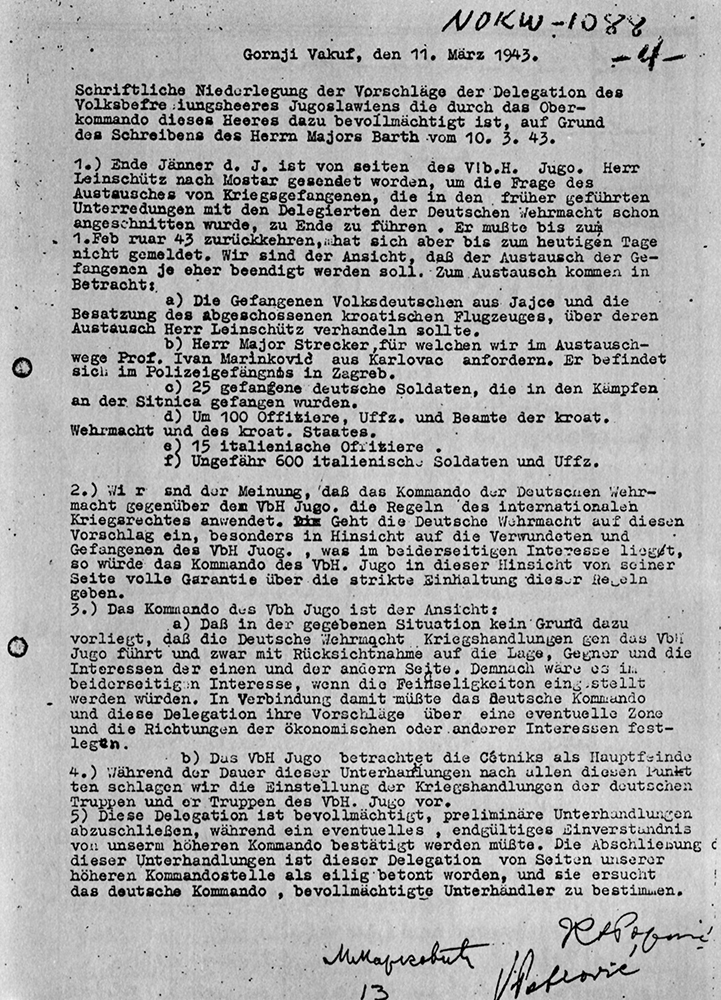

While collecting historical material in the United States, in the National Archives in Washington — specifically in the section for seized German archives from the Second World War — I obtained copies of most of the documents related to the negotiations between the Supreme Headquarters and the German military command. Among these documents is a written memorandum dated March 11, 1943, which reads:

“Gornji Vakuf, March 11, 1943

“Written memorandum of the proposals by the delegation of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia, authorized by the Supreme Command of that army, based on the record by Major Barth dated March 10, 1943.

“1. At the end of January this year, Mr. Leinschitz was sent by the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia to Mostar in order to finalize the matter of prisoners of war, which had already been touched upon in previous negotiations with delegates of the German army. He was supposed to return by February 1, 1943, but has not reported back to this day. We believe the prisoner exchange should be completed as soon as possible. The exchange should include:

“a) Captured Volksdeutsche from Jajce and the crew of a downed Croatian aircraft, which Mr. Leinschitz was supposed to negotiate about.

“b) Major Strecker, for whom we are requesting the release of Professor Ivan Marinković from Karlovac, currently held in police custody in Zagreb.

“c) 25 captured German soldiers taken during battles at Sitnica.

“d) Around 100 officers, non-commissioned officers and officials of the Croatian army and Croatian state.

“e) 15 Italian officers.

“f) Around 600 Italian soldiers and NCOs.

“2. We believe that the command of the German army should apply the provisions of international wartime law towards the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia. Should the German army accept this proposal — especially with regard to wounded and captured members of the National Liberation Army — which is in both sides’ interests, then the command of the National Liberation Army would, in return, offer full guarantees for strict adherence to those regulations.

“3. The command of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia considers:

“a) That, in the current situation, there is no reason for the German army to engage in military operations against the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia, particularly in view of the enemy’s position and the interests of both sides. It would, therefore, be in our mutual interest to suspend hostilities. In relation to this, both the German command and this delegation should present their proposals regarding a potential zone and matters of economic and other interests.

“b) The National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia considers the Chetniks to be the main enemy.

“4. While these negotiations are ongoing on all points, we propose a suspension of military operations by both German forces and the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia.

“5. This delegation is authorized to conclude preliminary negotiations, while any potential final agreement must be confirmed by our higher command. The urgency of concluding these negotiations has been emphasized by our supreme command and we request that the German command designate authorized negotiators.

“M. Marković K. Popović V. Petrović”

In addition to this brief version, Major Barth provided a more detailed one. In point 2 of this second memorandum, the issue of applying international law to captured and wounded members of the National Liberation Army by the armed forces of the Wehrmacht was specifically raised.

In the main document, which bears the number NDKW-1088/4, the first signature is that of Milovan Đilas, who — for reasons unknown — signed as M. Marković (I recognize Đilas’ handwriting and can confirm the signature is authentic). Next to Đilas’ signature is the name Vladimir Velebit, who signed as V. Petrović, likely to avoid using his real name so as not to endanger his elderly parents in Zagreb.

Only Koča Popović felt he could sign with his full name, as the commander of the 1st Proletarian Division, without hiding behind a pseudonym, even though he, too, had living family members.

During the talks between representatives of the Supreme Headquarters and the German command in Vakuf, it was agreed that the exchange of views would continue in Sarajevo and Zagreb. These negotiations were carried out by Milovan Đilas and Vlatko Velebit. On the night of March 18-19, Đilas — under the alias Miloš Marković, to which he added the title of Doctor and Professor at the University of Zagreb — arrived in Konjic and proceeded immediately to Sarajevo. In his memoirs, Đilas, as usual when it comes to matters involving himself and actions he is now ashamed of, is very vague and contradictory.

In a document dated March 20, 1943, which Đilas sent to the staff of the 1st Proletarian Division, he informed Tito that his business in Sarajevo had been mostly successfully completed in regard to the prisoners. A major prisoner exchange took place that same day in Konjic. Đilas then continued to Zagreb, where he held new talks, after which — at the end of March — a group of 16 of our imprisoned comrades was released.

The chief of staff of the German 717th Infantry Division, Dr. Krisch, also wrote a memorandum stating that the delegation of the Supreme Headquarters had expressed its desire to negotiate — within the scope of its authorization — on the following issues:

“1. Exchange of prisoners of war; 2. Application of international wartime law; 3. Other matters that were previously, on November 17, 1942, subject to negotiation with Captain Hevss, Captain Kulich and Mr. Ott (a civilian engineer who had been exchanged by the partisans). The National Liberation Movement delegation also drafted a written memorandum on-site in this spirit. Under point 1, several issues were mentioned. It is noted that ‘an exchange had already been carried out once. The continuation of negotiations was never completed. The delegate Leinschitz, who was sent a month and a half ago, has still not returned. Captured German experts from Jajce and the crew of an aircraft downed near Kupres, which was on a mission for the German Wehrmacht, were offered in exchange, along with Major Strecker, 25 German soldiers, 120 Domobran officers and NCOs and 600 Italian soldiers…’ Among the requests made by the delegation of the Supreme Headquarters, the record specifically underlines the demand for Professor Ivan Marinković (member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia) from Karlovac, held in custody by the Ustaše in Zagreb. It is also noted that the delegation pointed out that ‘it often happened that the German Wehrmacht — in connection with exchange actions — allegedly could not locate the requested individuals with the Ustaša authorities, or that they had already been executed by that time.’

“Regarding the second point of discussion — the application of international wartime law and the treatment of prisoners of war — the chief of staff wrote that: ‘The delegation emphasized that the National Liberation Army is an organized army with military discipline and is not a band. They fight as patriots and sons for the liberation of their homeland. They have always treated prisoners in accordance with international law — as has been the case since 1941. It was proposed that prisoners and wounded on both sides be treated humanely. The delegation undertakes to intervene should its units fail to comply with such instructions.’ As for the third point, the record refers to these issues as ‘political questions,’ noting the following: ‘This point had already been addressed once before — on November 17, 1942.’”

At the same time, the National Liberation Army provided guarantees that it would strictly adhere to international laws concerning prisoners of war. The third issue mentioned in the memorandum was presented as the opinion of the Supreme Headquarters of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia and expressed as follows:

“a) That, under the current circumstances, there is no reason for the German Wehrmacht to conduct military operations against the National Liberation Army, given the situation, the enemy, and the interests of both sides. Therefore, it would be in the mutual interest if hostilities were to cease. In this regard, the German command and this delegation should present their proposals concerning possible zones and positions related to economic and other matters.

“b) The National Liberation Army considers the Chetniks the main enemy.”

In point 4 of the aforementioned memorandum, a ceasefire between German troops and units of the National Liberation Army was proposed for the duration of the negotiations, while in the final point (5), it was emphasized that the delegation of the National Liberation Army was authorized only to conduct preliminary talks and that final agreement would have to be confirmed by the Supreme Headquarters.

On March 28, 1980, I spoke with Koča Popović, who — along with Peko Dapčević — was among Tito’s most respected commanders and who later served for eight years as Chief of the General Staff and for twelve years as Minister of Foreign Affairs.

I showed him all the documents I had brought from the National Archives in Washington, which are referenced in this chapter. Koča Popović stated that he had already seen those documents and, in terms of external identification, confirmed that they were authentic. He compared document 1082 (a translation of the authorization granted to each of the Yugoslav delegates on March 8, 1943, signed by Deputy Chief of the Supreme Headquarters Velimir Terzić) with the original authorization, which Koča had kept since the war. After comparing his original with document 1082, he confirmed that there was no difference. He made his original available to me for copying.

However, when he moved to the internal identification of the above-mentioned documents, he pointed out the arbitrariness and bias of the authors of document NDKW 1088/1, i.e. the German version of the talks with the delegation of the Supreme Headquarters. He noted that this bias becomes even clearer when document 1088/1 is compared with document 1088/4, which presents the views of the partisan delegation, written after the meeting and signed by all three delegates (Milovan Đilas, Koča Popović and Vladimir Velebit). Koča Popović told me that the two documents differ significantly, especially on key points in the German version of the conversation presented in 1088/1. Koča Popović believed this to be a critical issue, stressing that document 1088/4 more clearly reflects the position of the Supreme Headquarters delegation than what is conveyed in the tendentious German document 1088/1. He also added that Milovan Đilas, as head of the delegation and the one presenting its positions, did not do anything outside the directives they had received, but that it was clear he could have been more flexible. Koča said that he pointed this out to Đilas at the end of the talks.

During the negotiations — both in Vakuf and later in Sarajevo and Zagreb — German General Kasche informed Đilas and Velebit that “it would be beneficial if fighting ceased and unrest was eliminated in the area north of the Sava, as this would create the conditions for further discussions,” according to a German document I found. Another document states that General Gleise Horstenau told Đilas and Velebit that he wished to accomplish “something significant on behalf of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht.” According to that document, General Horstenau first requested that the partisans cease attacks on the Belgrade-Zagreb railway, which was a critical transportation route for the German army.

In the Collected Works of the Military History Institute, Vol. II, Book 8, page 359 (1959 edition), the instruction from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia dated March 29, 1943, sent to Iso Jovanović, secretary of the Provincial Committee of the Communist Party for Bosnia and Herzegovina, is published. The document was signed by Tito, Ranković and Sreten Žujović, and reads:

“Dear Iso,

“You may be surprised by the way this letter is being delivered. But don’t let that trouble you. We’ll explain everything when we meet. Here’s what this is about:

“With the 6th Brigade, reinforced by elements of the Majevica Detachment or the Fruška Gora unit, immediately move to the area between Goražde and Međeđa, on the Sandžak side, and clear the area of Chetniks in the direction of Zaborko and Čajniče. There you will establish contact with the left wing of our 1st Division and receive further instructions.

“During your movement — that is, during the crossing — do not engage the Germans, and do not take any action along the railway, as this is in the interest of our current operations. Before your crossing, send messengers towards Ustikolina, where they will link up with our units.

“Our most important task right now is to destroy Draža Mihailović’s Chetniks and to break up his administrative apparatus, which represents the greatest threat to the continuation of the National Liberation War.

“You’ll learn everything else when we meet.

“In eastern Bosnia, leave behind smaller detachments whose task will, for now, be fighting Chetniks and mobilizing new recruits. Reinforcements from the Majevica Detachment must not delay the movement of the 6th Brigade towards the direction outlined above.”

And in another document from the same volume — document no. 216, sent by Tito on March 30, 1943, to the Staff of the 1st Bosnian Corps, we cite the following passage:

“By using the contact established for the exchange of prisoners with the Germans, we managed to neutralize the Germans from the Chetniks and Italians. You must take this into account and direct all your fighting against the Chetniks in central Bosnia and Krajina, and defend only against the Ustaše — but only if they attack or assist the Chetniks. This is temporary — until further orders.

“Since Chetnik forces here are very strong, you must also transfer one division to eastern Bosnia to crush those bands. Your forces should move through central Bosnia and Ozren and must not carry out any operations along the way. We will send guides for this purpose.”

In Volume II of the Collected Documents and Data on the National Liberation War of the Yugoslav Peoples, from the Historical Institute of the Yugoslav People’s Army, Volume 9, document no. 161 contains the Order of the Supreme Commander of the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia, Comrade Tito, dated May 7, 1943, to the Main Staff of the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Croatia, concerning increased activity by units of the Third Operational Zone along the Belgrade-Zagreb railway. This document shows that attacks on the Belgrade-Zagreb railway had temporarily been halted:

“TO THE STAFF OF CROATIA

“Petrović was indeed in Slavonia at the time of the prisoner exchange, during the major battles around Konjic-Kalinovik. The attack on the railway had been temporarily suspended in the event of the transfer of the Slavonian Division to Bosnia, either due to the German-Ustaša offensive in Slavonia or for other military needs in Bosnia. He had arranged signals with comrades in the staff of the Third Operational Zone via Slobodna Jugoslavija. Operations along the railway must resume with full force and we will immediately issue orders via Slobodna Jugoslavija. Your forces have been inefficiently used in Slavonia. They are mostly focused on their own needs rather than engaging the enemy. Partisan detachments and sabotage groups are enough for railway destruction, while one or two brigades at most are needed for mobilization.

“The main battle is currently being fought here, with the aim of destroying Draža’s army. Our units near Nikšić delivered a crushing blow to the Italians and Chetniks — 470 Italians were killed, 500 Italians and 200 Chetniks captured. Seized were: Four 75 mm mountain guns, 70 machine guns and light machine guns, 20 heavy mortars, 7 tanks, 20 trucks, 5 cars and motorcycles, 5 wagons of mines, artillery and rifle ammunition, and 200 horses and mules.

“Tito”

Member of the Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Uglješa Danilović, kept a very detailed diary during the war. On April 1, 1943, in the village of Nišić in eastern Bosnia, he recorded the following:

“But with the 1st Battalion came a major surprise for us. A delegate of the Supreme Headquarters arrived for the exchange of German prisoners, accompanied by two Germans — a German captain and a civilian. He told us things we initially did not believe. But after providing numerous details confirming his identity, we believed what he said. This concerns a significant change in tactics — but I’ll write about that later, when the time comes. He also informed us of the following: A courier from the Supreme Headquarters had been dispatched with an order for us. The courier left this morning at 6 a.m., accompanied by two Germans, riding a motorcycle to Šekovići. Our comrade gave us a brief summary of the order’s contents. The 6th Brigade is to move towards Čajniče, crossing the Drina between Međeđa and Goražde, with the objective of attacking from the flank.

“An order was immediately given to prepare a company to depart early in the morning to Šekovići, which would bring the order. I must note that this courier took advantage of the negotiations with the Germans over prisoner exchange to travel this route. One company was immediately sent to Kalauzovići to establish contact with the Group of Assault Battalions. They were ordered to halt the movement that had previously been planned. We scheduled a meeting for 10 a.m. tomorrow in Rakova Noga. The comrade with the Germans immediately returned via Srednje to Sarajevo. A company was assigned to escort them.”

Uglješa Danilović arrived on April 4, 1943, in the village of Govza, where the Supreme Headquarters was located and where he spoke with Tito, who told him:

“Especially if the Allies land in the Balkans, the Yugoslav government in London may try to exploit the situation to reap the rewards of our struggle.”

On November 15, 1972, Uglješa Danilović sent me a letter providing clarification, so that what he had written in April 1943 could be better understood. The letter reads:

“Comrade Vlado,

“I’m sending you two pages from the typed version of the Diary. The entry regarding the 6th Velebit Brigade is dated April 1 — Nišić.

“You’ll see from the text that it can only be properly understood in connection with what I wrote on April 16, 1943, in the village of Govza (that text is in the manuscript I sent you). In the April 1 note, I didn’t clearly or specifically state what Vlatko told us — instead, I camouflaged it with the sentence: ‘This concerns a significant change in tactics…’ I did this for reasons of secrecy, fearing my diary might fall into enemy hands. But I also did it because I wasn’t yet fully convinced that what Vlatko told us was true. From all of this, one could conclude that Vlatko really was speaking in terms of a truce. What was actually going on is made perfectly clear in Tito’s words, which I recorded immediately after our conversation.”

In 1965, I sent copies of the aforementioned documents from the seized German archives, housed in the National Archives in Washington, to Tito for his memoirs. The documents were delivered in person by Vlajko Begović, head of the Commission for Collecting Material for Memoir Literature, i.e. for Tito’s memoirs. On that occasion, I did not meet Tito myself so I could not hear his thoughts on those documents.

When I spent almost an entire day with Tito on November 1, 1978, discussing the history of our revolution, I had prepared a question regarding those documents. My impression was that Tito did not have all the documents related to the 1943 incident at hand — particularly his own order concerning the halt of operations in eastern Bosnia and Slavonia, which had already been published over 20 years earlier in volumes of the Military History Institute. Tito replied sharply that the negotiators had exceeded their authority. Finally, as we were parting, Tito suggested that we should meet again, this time with all the materials, to go over every document.

In June 1979, I received a phone call from Berislav Badurina, head of Tito’s cabinet, asking if I was ready to meet with Tito in three days to review all the documents regarding the March negotiations with the Germans, with two other Yugoslav historians present — both of whom had also been collecting material on this historic event for many years. Since I was already prepared for the meeting, I agreed, and the date was set for the end of June. However, the meeting was postponed because one of the historians couldn’t attend — he was abroad at the time.

A second meeting was scheduled for October 1979, but at Tito’s request, it was postponed again, presumably due to his health condition.

For the planned 1979 meeting with Tito, I had prepared my analysis of the March 1943 negotiations, along with all the documentation I had gathered from foreign and domestic archives. (It is important to note that Tito’s key documents had already been published in the volumes of the Military History Institute.) My points were as follows:

1. Common sense demands that historical truth take precedence over political truth. All documents — German and ours — should be published, accompanied by critical commentary, and only then can we draw conclusions. There is no history without historical facts. Even Karl Marx, before arriving at the conclusions and analyses in Capital, first gathered reports from factory inspectors in England about the exploitation of workers, and only then did he provide his analysis.

2. Withholding documents is not very intelligent because all German war documents are available to archives around the world. If a document is suppressed today, what will we do when we’re no longer around, when we can’t ban anything anymore? We’ll be ridiculed by history, and because of that one forbidden document, many other great things about our revolution could be questioned.

3. My central hypothesis regarding the 1943 negotiations is this: Based on the documents I’ve reviewed, I am convinced that the most aggressive factions in Britain, especially the group around the Special Operations Executive (SOE), were preparing an armed intervention in Yugoslavia with the help of the occupiers and Chetniks. Of all the European countries where resistance movements fought the occupiers, the deepest social transformations occurred in Yugoslavia, Greece, and to an extent Albania. These were in fact revolutionary wars in which new governments were being built. That’s why it is no coincidence that right-wing elements in Britain chose Yugoslavia to be the first victim of intervention — to destroy us under the guise of “liberation” during the Allied invasion. What they tried to do in Yugoslavia in 1943, they succeeded in doing in Greece in 1944.

4. The current ideological focus on the anti-Hitler coalition should not blind us to the true class nature of Britain. It is the oldest colonial power and Hitler’s attack on Britain did not suddenly make it anti-imperialist. Other major powers in the anti-Hitler coalition were also hegemonic — just like Britain. This became especially clear in the second phase of the war, after Stalingrad and Rommel’s defeat, when it became evident that nazi Germany’s defeat was near. At that point, the struggle among the great powers within the Allied coalition for the division of the world became even more pronounced.

5. It is important to note that during the March negotiations, Hitler had already decided to destroy the core of the partisan forces, preparing for the final phase of Operation Schwarz. While negotiations and prisoner exchanges were underway, German, Italian, Ustaša and Bulgarian units were encircling the Durmitor massif, where the main partisan forces, along with 4,000 wounded, were located.

6. The remaining Montenegrin Chetniks, led by Pavle Đurišić, were disarmed by the Germans at the beginning of the Fifth Offensive, but he was soon released, and until the end of the war in 1945, Draža Mihailović’s Chetniks operated in coordination with German forces throughout Yugoslavia — especially in Serbia.

7. It is also important to emphasize that Tito believed that no Allied army could enter Yugoslav territory without the permission of the Supreme Headquarters and the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ). This applied even to the Soviet Union, and Tito concluded a special agreement with Stalin in late October, allowing Red Army units to enter Yugoslav territory — with provisions for their eventual withdrawal.

During 1943 and 1944, Tito issued several orders that no one was to violate Yugoslav territory. For these reasons, American planes were shot down in 1946 — aircraft that had deliberately breached Yugoslavia’s territorial integrity, even though the U.S. government had been warned multiple times not to do so.

When Tito met Stalin for the first time, at the end of September 1944, he told both him and Molotov, upon hearing that some British units had landed in Yugoslavia, that they would be thrown into the sea.

8. No agreement for a ceasefire or truce was signed with the German representatives. The only agreement signed was to create a neutral territory in Pisarovina to facilitate prisoner exchange.

My personal opinion is that the March 1943 negotiations were unnecessary, except for the prisoner exchange. From the partisans’ perspective, nothing was achieved — not even in terms of military deception. According to plans for specific phases of the Fourth Offensive, German forces had no intention of crossing the Neretva River, as that zone was under the operations of Italian and Chetnik troops. Berlin’s main concern was to secure the bauxite mines between Mostar and Imotski so that aluminium production in Germany would not be interrupted.

That is my hypothesis. Some documents support it, and it is up to younger historians to gather all material — German, British and Yugoslav — and determine whether it is justified.

All of this further confirms the importance of the methodological principle of the theory of distance — that contemporaries of an event cannot also be its historians.

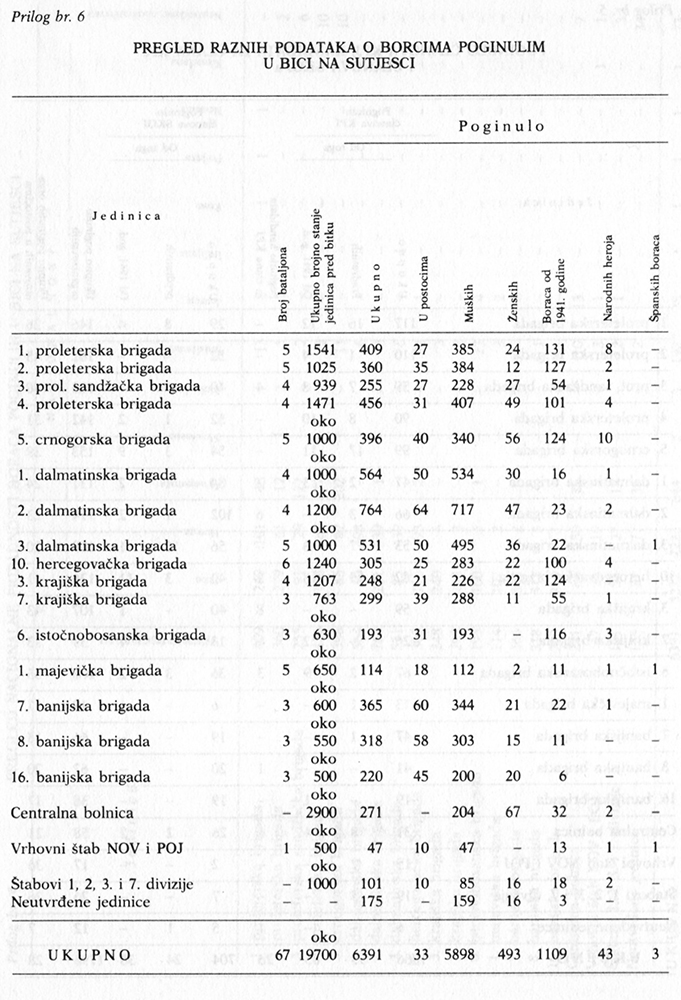

The German command carried out its troop concentration for the Fifth Offensive in complete secrecy. Until the very last moment, it didn’t even inform its allies, the Italians. For the partisan Supreme Headquarters, the Fifth Offensive was a major surprise. The order for the Fifth Offensive was issued by General Lötters only on May 6, 1943. He estimated that the partisan forces inside the encirclement numbered around 15,000, which was a fairly accurate figure. (The main operational group had just over 16,000 fighters, while over 4,000 partisans were in the Central Hospital as wounded or suffering from typhus.)

Lötters concentrated around 70,000 German soldiers (the 1st Mountain Division, the 7th SS Division Prinz Eugen, the 118th Jäger Division, and elements of the 369th and 104th Jäger Divisions, as well as the Brandenburg Regiment). He also counted on three Italian divisions — Taurinense, Venezia and Ferrara — along with smaller elements of other Italian divisions. Pavelić made available about 11,000 of his troops, and the Bulgarian Minister of War approved the use of Bulgarian troops outside their occupation zone in Serbia, on the territory of Montenegro. This included the 61st Bulgarian Regiment, with another Bulgarian regiment also ready to participate in the operation. In total, Lötters had just over 100,000 troops for the Fifth Offensive. The air force was deployed in greater numbers than during the Fourth Offensive.

The German command planned the first phase of the operation (deep encirclement) to last ten days, the second phase (destruction of partisan forces within the pocket) another ten days, and a few additional weeks to thoroughly sweep the area and completely destroy the main partisan forces.

Unaware of what was being prepared, the Supreme Headquarters held a meeting on May 8 in the village of Kruševo, in the Piva valley, where they discussed continuing the partisan offensive, possibly pushing into Kosovo and towards the borders of Serbia. Meanwhile, the first reports about German concentrations began to arrive, which the acting chief of the Supreme Headquarters dismissed as unfounded. He trusted the March negotiations with the Germans too much and believed it was impossible that the Germans would attack. He even mocked the command of the 10th Herzegovina Brigade, which had sent a report on the German troop concentration, replying disdainfully: “Watch those Herzegovinians — they saw a few Domobrani in German uniforms and got scared.” It was only on May 15, when the German air force and ground assault units launched attacks from all directions, that it became clear a new major offensive had begun.

The Main Operational Group’s units could have easily broken through the encirclement if it weren’t for the issue of the wounded and typhus patients. Because of that, the Supreme Headquarters had to consider the fate of the wounded, and the divisions’ mobility was thus hindered. Another decisive battle had to be fought inside the enemy’s pocket — initially to save the wounded, and in the second phase to save the Main Operational Group itself.

German commanders issued special orders stating that not only armed partisans but also civilians in the encircled area should be exterminated and that all water sources should be poisoned. Therefore, from the very beginning of the Fifth Offensive, the Supreme Headquarters issued an order to all rear military authorities and operational units to inform the population to flee into refugee columns, to the impassable parts of Durmitor, Sinjajevina and other surrounding mountains.

After the first clashes in the Lim and Drina river valleys, the Supreme Headquarters decided that the way out of the offensive should be sought by breaking through to the north, towards Bosnia. An order was issued to abandon the direction towards Serbia and not to attack Mojkovac and Kolašin. The first direction of the partisan breakthrough was towards Foča, where the 1st Proletarian Brigade had been transferred, but German forces put up stiff resistance on that front.

The movement of partisan units was also slowed down by the expectation that a British military mission would soon arrive at the Supreme Headquarters. Already in April 1943, British military authorities had sent three missions into the territory under Croatian and Bosnian partisan control. One of these missions was led by Major William Jones. Through this mission, the British military command in the Middle East informed the Supreme Headquarters that it intended to send a mission directly to them, which was accepted. The arrival of the British military mission was initially scheduled for May 22, in the free territory near Žabljak, but it was postponed to the early morning of May 28. As a result, the Supreme Headquarters lost six valuable days.

The British mission was led by Major William Stewart and Captain William Deakin. The latter was a personal friend of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his adviser on historical matters.

Even before the British mission’s arrival, the Supreme Headquarters had sent a radiogram to the Main Staff of Croatia, instructing them — through the British mission — to request that the Allied military authorities immediately bomb the staging bases of German and Italian troops involved in the Fifth Offensive, located in Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje, Derane, Andrijevica, Podgorica, Nikšić and Mostar. But the British command ignored this request.

By late May, the Supreme Headquarters realized that the breakthrough to the north would not be possible in the Foča sector. The Sutjeska valley was then chosen as the best location for the partisan forces to break through the German encirclement. The Supreme Headquarters recognized that the Vučevo plateau — between the canyons of the Drina, Sutjeska and Piva rivers — was the key to the Sutjeska valley, and sent the 2nd Proletarian Brigade to seize this strategically vital point. Serbian and Bosnian proletarians reached the top of Vučevo just minutes before the Germans and pushed them down into the Sutjeska valley. At the same time, on all other sectors, German troops advanced, tightening the encirclement around the Main Operational Group and the 4,000 wounded.

Tito kept Moscow fully informed of the situation. His radiograms best reflect the severity of the position the Main Operational Group found itself in. Some of them contain elements reminiscent of Bishop Danilo’s monologue in The Mountain Wreath.

Tito also informed Moscow of the British mission’s arrival and pleaded for Soviet support. In a radiogram dated May 23, 1943, Moscow asked for details — whether we had airstrips in the liberated territory and whether we had aviation fuel. The Soviets were considering sending aircraft, but due to the distance from the Soviet front, any planes would have to land on Yugoslav territory.

Tito responded to Moscow on May 24, saying that the arrival of the British military mission was expected, and then requested that a Soviet military mission also be sent:

“In this regard, we ask the Supreme Command of the Red Army to also send its military representative as soon as possible. As for sending your plane — it could easily land in the area around Žabljak, but the front is now close by and we do not know how long we will remain here. We have no aviation fuel, but your representative could parachute in. As soon as we find a suitable location, we will inform you of the landing possibilities.”

At the same time, Tito conveyed to all commanders and fighters his determination that the partisans must break through the German and collaborationist encirclement at all costs. I recorded the following in my Diary on June 5, 1943:

“Koča and Peko came for a consultation with the Old Man. They sat under a tent flap, rain constantly lashing them. They were deliberating. After the meeting ended around noon, I approached Peko and asked what I should write in the Diary. He laughed:

“‘Write: we will break through! And period.’”

Meanwhile, German troops had taken all of the Sandžak and our units had crossed to the left bank of the Tara River. The Germans made changes to their operational plan. Realizing that the partisans had decided to break through at Sutjeska, they began urgently transferring unit after unit there. The Supreme Headquarters decided to split all forces into two groups: the 1st and 2nd Divisions with ten brigades would break through across Sutjeska into Bosnia, and the 3rd and 7th Divisions with six brigades and the wounded would head back across the Tara River into the Sandžak. The Supreme Headquarters would be with the first group and the AVNOJ Executive Committee with the second. At the same time, a message was sent to the Bosnian Corps to move south in order to hit the Germans from behind and ease the breakthrough of the main forces.

An order was issued to bury all heavy weapons to speed up the movement of partisan units, but this measure also weakened their firepower. Hunger once again ravaged the partisan ranks. The fighting took place in almost uninhabited areas. What few houses existed had already been destroyed in the early months of the war.

The Germans managed to seize the upper course of the Sutjeska, but failed to take the Gornje and Donje Bare plateau, defended by the 2nd Dalmatian Brigade. From June 6 to 8, one of the hardest battles of Sutjeska was fought there. The command of the 2nd Battalion of this Dalmatian brigade sent a report on June 8:

“The Germans are attacking with increasing force and persistence — we have lost two-thirds of our men, but count on us as if we were at full strength.”

The 2nd Operational Group, under the command of Milovan Đilas, however, could not cross the Tara and decided to go with the wounded to join the first group, which held only a narrow strip between Suha and Tjentište at Sutjeska. The Supreme Headquarters crossed the Sutjeska and, on June 9, ascended the first slopes of Zelengora. The German air force heavily bombarded the entire area and the partisans suffered many casualties. Among those wounded was the Supreme Commander, Tito. One of the British mission leaders, Stewart, was killed, and the other, Deakin, was wounded.

German aviation bombed the Supreme Headquarters almost daily. Only after the war, when General Löhr, commander of the German Southeast Front, was captured, did it become known that German radio triangulation stations had, during the Fifth Offensive, precisely located the Supreme Headquarters by tracking its radio transmissions. The radio station had to maintain daily contact with the Comintern radio in Moscow at the same time each day and for extended periods. Once the location of the Supreme Headquarters’ radio station was determined, it was sent to German air force commands, which then bombed the area very accurately — especially since the partisans had no anti-aircraft defense at all.

The 1st Proletarian Brigade, under the command of Danilo Lekić, took the initiative and, without waiting for contact with the divisions behind, broke through the German front at Balinovac at dawn on June 10. The entire 1st Proletarian Brigade deployed in a skirmish line and stormed the German positions. General Löhr informed the German Supreme Command the same day:

“After heavy and uneven fighting, the enemy has succeeded in making a local breakthrough on the front of Combat Group of the 369th Legionary Division.”

That same day, some Italian prisoners — who had been working as handlers for the Supreme Headquarters — defected to the enemy. (Vladimir Nazor’s handler took with him the original diary of the old poet and delivered it to the Germans.) This was made easier by the fact that the front line was often only a hundred metres from the location of the Supreme Headquarters. These men also informed the German command about the movements of the Supreme Headquarters, which reported to Berlin:

“A strong enemy force in Sutjeska-Piva has been squeezed into the tightest area. It is confirmed that Tito is among them. This is the final phase of the battle. The moment for complete destruction of Tito’s army has come.

“Importance of the order: No man capable of military service may leave the encirclement alive. Women should be checked to ensure they are not disguised men — this must be reiterated to the troops.

“Tito and his entourage are reportedly wearing German uniforms. Check soldiers’ military booklets.”

The 1st Proletarian Division, under Koča Popović’s command, took advantage of the tactical breach and quickly widened it, reaching the Foča-Kalinovik road on June 12, which it also crossed. The German ring was now behind it.

The German Supreme Command issued new orders to tighten the ring, and on June 12, General Lötters personally arrived on the Foča-Kalinovik road to raise troop morale. But the second wave of the Main Operational Group was already advancing on this route. Before the breakthrough, Tito sent a radiogram to Moscow:

“We are still in a difficult position. The enemy is again trying to encircle us. On the route of our advance towards central and eastern Bosnia, the enemy has occupied and fortified all the high ground, placing artillery, machine guns and small garrisons, and with their main forces is trying to encircle us. They are attacking constantly from all sides. The enemy is suffering heavy losses — but so are we, especially from aviation. On June 9 and 10, we suffered great losses. On that day, British Captain Stewart was killed by an airstrike, and Captain Deakin and I were slightly wounded. I was wounded in the arm by shrapnel. Captain Stewart was the head of the British mission at our headquarters. The British say they could not imagine the severity of the battle we are fighting. They see that our units are in combat during the day and on the move at night. They do not sleep or eat. They now eat horse meat without bread.

“Our situation is difficult, but we will get out of it, although with heavy losses. The enemy is making maximum efforts to destroy us, but will not succeed.

“We ask for your support in this most difficult ordeal.”

The main breakthrough of the 2nd Division, together with the Supreme Headquarters, began on the night of June 12, and on June 13, the main force crossed the Foča-Kalinovik route. That section was defended by a German tank unit. Fighters from the 2nd Proletarian Brigade refused the order to bury their heavy weapons and carried a single anti-tank gun — with only three shells — through the enemy ring. They hid it in a hedgerow by the road and waited for the enemy tanks to approach to within ten metres. With two shots, they disabled two tanks and the rest withdrew. Meanwhile, the 7th Banija Division managed to reach the 2nd Division and also broke through across the Kalinovik-Foča road.

However, German forces received reinforcements and closed the ring again at Sutjeska, on Zelengora and on the Foča-Kalinovik road, so that the 3rd Division, burdened with severely wounded, could not break through. The 1st Dalmatian Brigade had reached Sutjeska by June 12 and taken Tjentište by storm but was unable to hold the positions until the main force of the 3rd Division arrived. It broke out independently in small groups towards the north.

The 3rd Division had its last radio contact with the Supreme Headquarters on June 12, and at dawn on June 13 began crossing the Sutjeska. Combat units were mixed with the wounded and refugees. The Germans had their fire concentrated on every metre of the mountain river. They let the partisans get very close, then opened fire. Exhausted and starving, the fighters faltered. The order came: “Communists, forward!” And in the first charge, the commanders led by Sava Kovačević rushed ahead. That day, the 3rd Division lost half its strength at Sutjeska. After Sava Kovačević was killed — struck in the forehead by a bullet in front of an enemy bunker — chaos erupted in the unit, which began to break out in smaller groups.

Holding to the partisan rule that one must not fall alive into enemy hands, many severely wounded fighters committed suicide. As I mentioned earlier, the political commissar of the 3rd Sandžak Brigade, Božo Miletić, was wounded during the breakthrough. He felt his shattered femur, called out to his comrades: “Forward, I don’t want you dying because of me,” and placed a revolver to his temple. A few minutes later, a deputy battalion commander was wounded; calmly, he took out his revolver and shot himself — so as not to burden his comrades during the escape.

In Piva and Sutjeska, German and Italian troops executed over 1,300 wounded partisans, as shown by German and Italian military documents seized after the war. The medical personnel of the Main Partisan Operational Group shared a similar fate. Around 200 nurses and 30 doctors died at Sutjeska. That was half of the qualified staff of the Central Hospital.

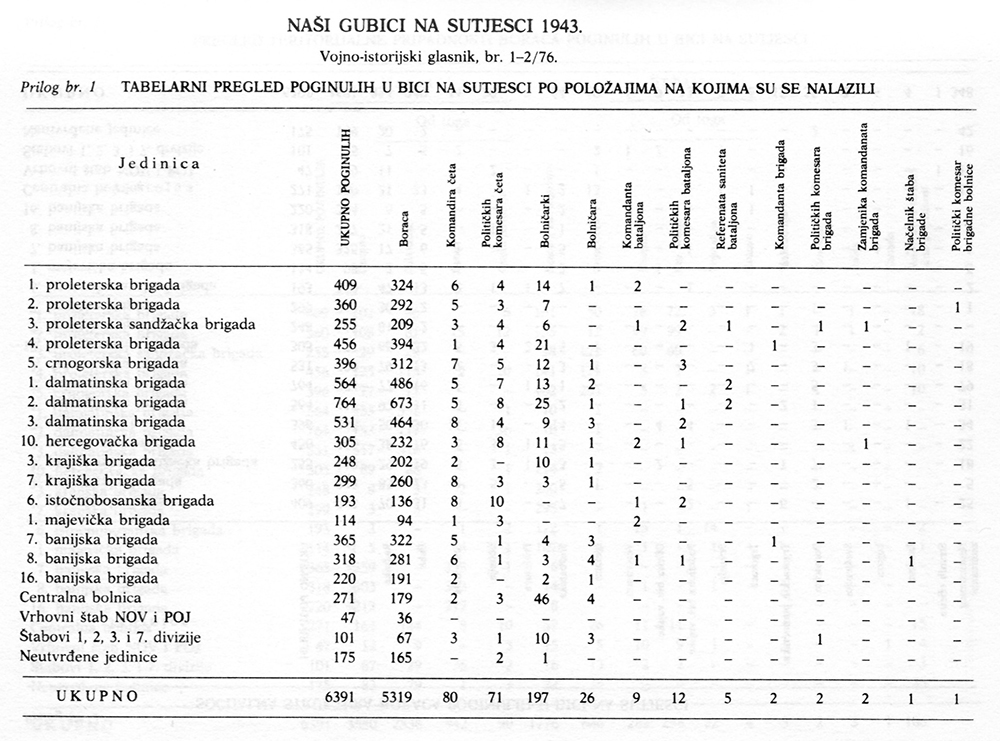

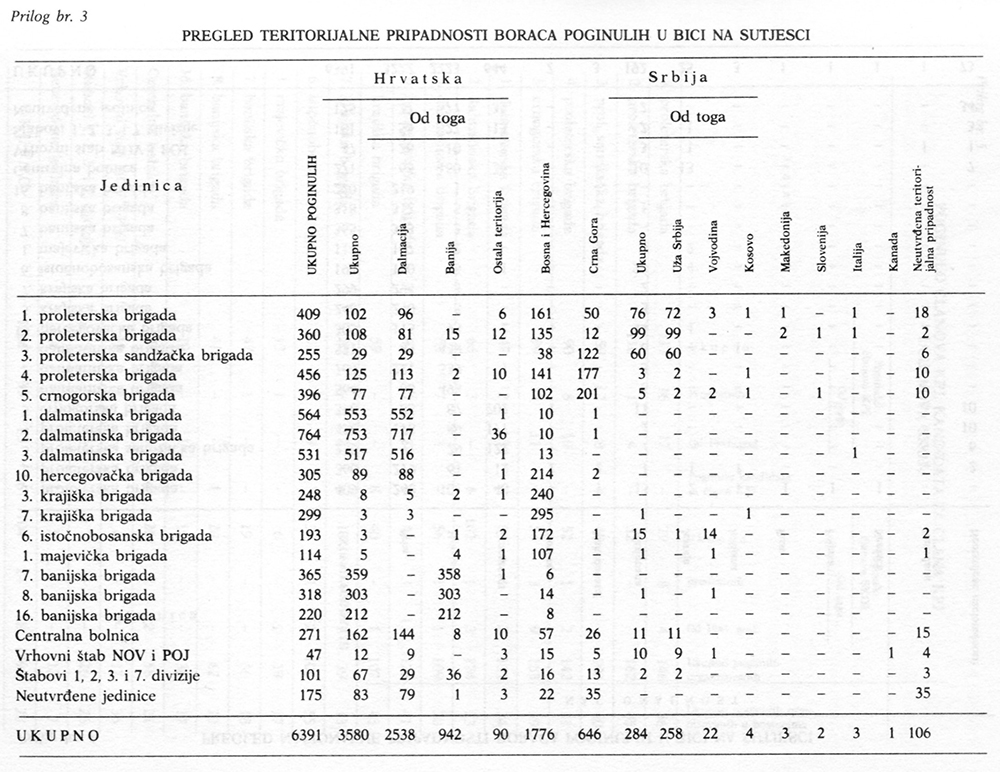

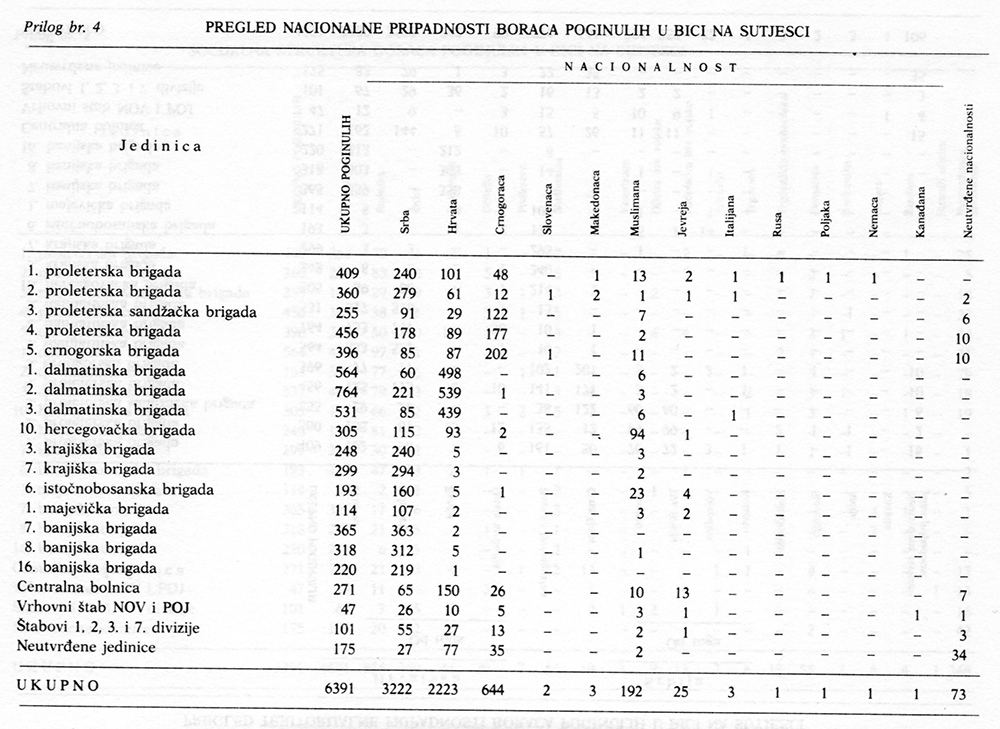

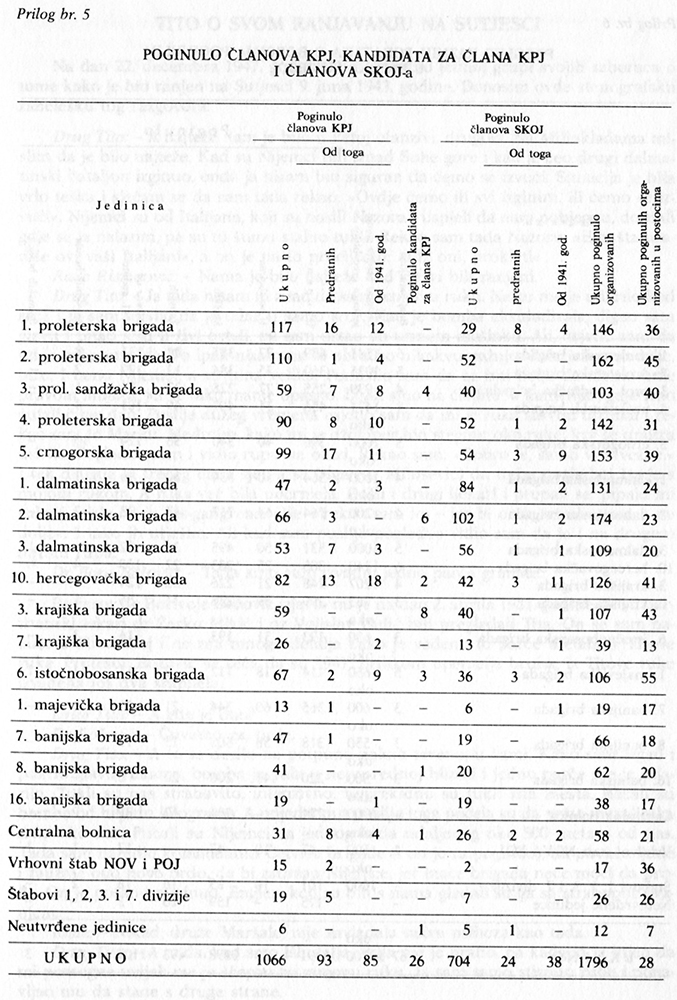

Total partisan losses at Sutjeska amounted to over 6,000 people. It is estimated that more than 30 per cent of the Main Operational Group’s fighters were killed in the Battle of Sutjeska.

The exact number of civilians killed in refugee columns is unknown. The German SS Division Prinz Eugen massacred several refugee groups in its sector, which included between 50 and 580 women, children and elderly people. The Italian Ferrara Division also brutalized the population. The Bulgarian 61st Regiment executed 20 people in the village of Palež near Žabljak. In the Durmitor district alone, in Montenegro, 1,200 civilians were killed, 5,000 homes were burned and about 60,000 head of livestock were looted.

After breaking through the encirclement at Sutjeska, the Main Operational Group quickly pushed forward towards Jahorina and Romanija, liberated Han Pijesak, Vlasenica, Drinjača, Srebrenica, Kladanj and Zvornik. New weapons were seized from the enemy.

The German command had to admit that its goal in the Battle of Sutjeska was not achieved. General Löhr later said: “The initial objective to free German troops tied down in Yugoslavia and send them to the Eastern Front was not achieved at all. On the contrary, by the end of the operation, new German forces and commands had to be brought in.”

The Battle of Sutjeska once again confirmed how crucial the moral and political factors of the partisan army were. But these operations also showed that the fighting qualities of the soldiers and commanders, as well as their military skill, were at such a level that they could defeat such experienced military commanders and such a disciplined army as the German one.

Tito was the only Allied commander wounded on the battlefield. This happened on June 9, 1943, in the thick of the Battle of Sutjeska. I wrote the following about it in my Diary:

“Below Milinklade. I had just closed my eyes when bombs started exploding. Across from us, about fifty metres away, a scout threw grenades at live targets — at the battalion of the 4th Brigade. Shrapnel sliced the branches above us, but the column of Montenegrins didn’t stop — they just picked up their pace. And no one was hit. Then the Stukas came — nine of them. They bombed Milinklade and the Hrčavka valley. At eleven o’clock, Dornier bombers appeared. Bombing in the forest is dangerous. The bombs shatter on the branches and shrapnel flies from all directions. We were lying in a damp gully, a stream soaking our feet, checking our watches to see when this terrible day would end.

“In the afternoon, a letter arrived for Uncle Janko and Vlatko. Both of them turned pale:

“‘The Old Man is wounded. The Englishman is dead…’

“The entire Escort Battalion immediately went up, as Marko had reported they were without protection and the Germans were close.

“Bombs kept falling around us. Suddenly I heard someone calling:

“‘Comrade Vlado, Dedijer…’

“All dishevelled, red-faced, breathless, nurse Ruška from Olga’s surgical team was running towards me:

“‘Comrade Vlado, Olga is calling you to carry her. She’s badly wounded…’

“Uncle Janko told me I could go. Ruška had calmed down.

“‘A bomb fell right in the middle of the surgical team. Olga’s shoulder was blown off. She’s a wonderful doctor. She told us: “Go on, leave me, don’t get caught by the Germans because of me…” What upset her most was that all the medical supplies were destroyed…’

“We quickly climbed up Milinklade. Wounded were descending en masse. Ruška told me that more than a hundred comrades from the 4th Brigade had been killed or wounded that morning on the hilltop, where aviation had spotted them in a clearing.

“Bombers returned. Wounded fighters were descending in groups down Milinklade. The Stukas flew so low they skimmed the treetops, dropping bombs. Then came the spotter planes, dropping anti-personnel bombs. Suddenly the roar of engines deafened us. Ruška and I dropped to the ground. Seven or eight bombs landed around us. The smell of gunpowder choked us. Total darkness. When the smoke cleared a bit, I saw beside me a comrade from the 6th Bosnian Brigade — a young man with large black eyes. Both his legs had been blown off. Blood gushed, carrying away young beech leaves shaken loose by the explosion. We couldn’t help him. He was dying slowly. He waved to me and whispered:

“‘Long live Stalin!’

“I continued climbing. Under an oak tree, about twenty metres above us, sat Olga. Her entire shoulder was bandaged, blood seeping through. She looked at me with her deep black eyes and tried to smile:

“‘Don’t worry! Yes, it’s a serious wound.’

“The nurses had tied off her arm with a rubber tube, but she had removed it — it felt better. Then she slowly started down the hill. Two comrades supported her. She walked the steep slope herself, since a horse couldn’t make the descent. We helped her all the way down into the Hrčavka valley.

“Darkness was falling, the bombers came again, dropped their bombs and then the long-awaited silence came. Fires appeared all over the Hrčavka valley. I sat beside Olga and fed her hot soup given to me by one of our units. Olga Milošević showed up with an anti-tetanus injection. That day, a German bomb had hit our pharmacy directly. It destroyed all the medicine, except — by sheer luck — this one vial. Olga received the injection. At that moment, the Old Man was coming down the hill, with Marko behind him. The Old Man’s arm was bandaged. He stopped beside us and asked:

“‘How are you, Olga, are you badly wounded?’

“Then he went with Marko across Hrčavka, uphill towards Debela Ravan.

* * *

“Olga told me that many good comrades had died that day on Milinklade:

“‘Vako, our brigade commander, is seriously wounded!’

“It was time to move. Olga was given a horse, but she couldn’t cross the Hrčavka riding. The horse might panic and she could fall into the water. I stood on the bank, wondering how to carry Olga across. Suddenly, Mićo Janković, deputy commander of the Escort Battalion, appeared:

“‘We’ll carry Olga together!’

“And so we crossed to the other side of Hrčavka and began climbing Debela Ravan. The path was unusually narrow with an abyss below. In several places, we had to lift Olga off the horse. I had to find the way in total darkness, waving a burning stick in front of me. Olga walked on her own in many spots, then got back on the horse when she grew tired. For three hours, we climbed in pitch darkness.

“Long after midnight, we emerged onto a plateau and found some of our brigades and field hospitals asleep. I shouted into the night, asking where the hospital of the 4th Brigade was, but the comrades slept like they were turned to stone from sheer exhaustion. I walked towards some dying fires, calling out at the top of my voice, but no one answered — everyone had collapsed from fatigue and was sleeping heavily. Finally, from one fire that had not yet gone completely out, a tall man rose and asked me:

“‘What do you want, comrade?’

“It was Boro Kovačević. I didn’t recognize him at first. When he heard I was bringing Olga, he came with me and helped me lay her down on the ground. She leaned against a beech tree and Boro and I sat next to her and talked quietly. Boro spoke about Klim Samgin, about the days leading up to the war in 1939. We talked like that for a full hour. Someone began waking the soldiers and the wounded, a commotion began, horses started being loaded and the column moved forward. As we parted, Boro said to me:

“‘After the war, I’d really like to go back to translating Klim Samgin.’”

And in my book on Tito from 1952, I described how Tito was wounded and noted his state of mind at that moment:

“The Supreme Headquarters was passing through a large clearing, scarred by artillery shells and aerial bombs, when German scout planes appeared and dropped a dozen anti-personnel bombs. There was no shelter in that place. Everyone hit the ground where they stood. A light machine-gunner named Petar from Mrkonjić-Grad was killed there.

“The German planes flew very low — you could even see the pilots’ faces. The first bombs fell. Tito took cover behind a massive beech tree that had been toppled long ago by a storm. He lay beside the stump, stretching his body along the fallen trunk. Behind him was the English captain Stewart. Marko was three or four steps away.

“When one bomb, weighing around ten to twenty kilograms, whistled down towards where Tito was, his dog Luks leapt onto Tito’s head at that very moment and shielded it with his body. The bomb struck the stump, just one metre above Tito’s head.

“The explosion hurled Tito and the others nearby into the air. When the smoke cleared, several motionless bodies lay on the ground. Among them were Đuro Vujović, Tito’s escort and a veteran of the Spanish Civil War who had fought for 22 months behind Franco’s lines, and English Captain Stewart.

“Later, Tito told me how he felt in that moment:

“‘It hit me good… I thought it was the end…’

“He smiled slightly, then continued:

“‘I was behind a fallen beech; when the bomb slammed next to me and darkness surrounded me, for a moment I thought I was dead. My dog Luks, who had covered my head with his body, lay torn apart… A bit further away was Captain Stewart, his legs sticking straight up… Even farther, Đuro… In the middle of all that devastation, my eyes fell on a broken tree and on it, a tiny forest bird was chirping sadly. The explosion had broken its leg and injured its wings… The little creature stood on one leg, fluttering its wing. That image is etched deeply in my memory… Then Marko came up and took me by the arm…’”

(Translated from the Serbo-Croatian: Vladimir Dedijer, New Contributions to the Biography of Josip Broz Tito, Vol. 2, Liburnija, Rijeka, 1981, pp. 801-820.)

Charts on Losses at Sutjeska 1943

Documents